It is hard to grasp a painting that does not let you grasp it using the usual approaches, which are the relation to modernism and postmodernism, going beyond figuration, and the return of the latter, that is being endlessly postponed, announced, vilified, and foiled. As a rule, to broach a pictorial work, one attempts to make ever more subtle classifications, which try to pin the painter down within one category or another, rather in the way that people have always tried to classify animals in order to objectify them and make them subjects for study. So, in painting, there are two great reigns, that of abstraction and that of figuration, which have been violently clashing for more than a century and a half, […]

It is hard to grasp a painting that does not let you grasp it using the usual approaches, which are the relation to modernism and postmodernism, going beyond figuration, and the return of the latter, that is being endlessly postponed, announced, vilified, and foiled. As a rule, to broach a pictorial work, one attempts to make ever more subtle classifications, which try to pin the painter down within one category or another, rather in the way that people have always tried to classify animals in order to objectify them and make them subjects for study. So, in painting, there are two great reigns, that of abstraction and that of figuration, which have been violently clashing for more than a century and a half, ever since Manet, Cézanne, and Kandinsky. Alun Williams’s painting seems to thwart this kind of slightly cursory classification, not because his paintings are revolutionary in the sense that they mix figuration with abstraction, which has become a rather commonplace position in the postmodern era, but because they borrow from both these systems, while at the same time pushing back, a little bit further, the boundary of their conflicting coexistence inside the picture.

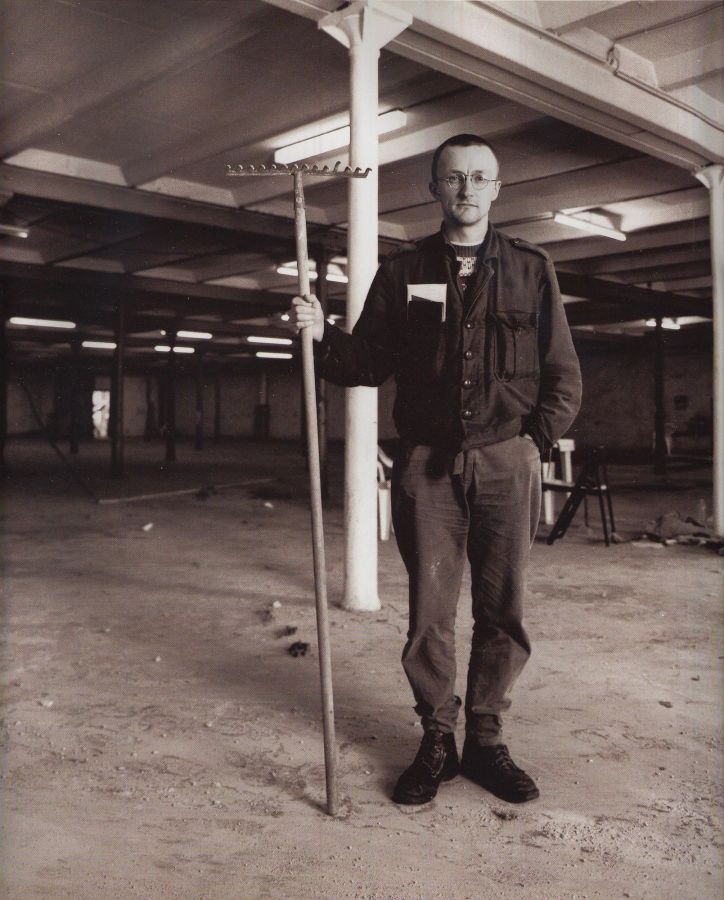

Alun Williams par Patrice Joly

Excerpt of a text published in zerodeux Nº93, 2020