La Forme Naturelle

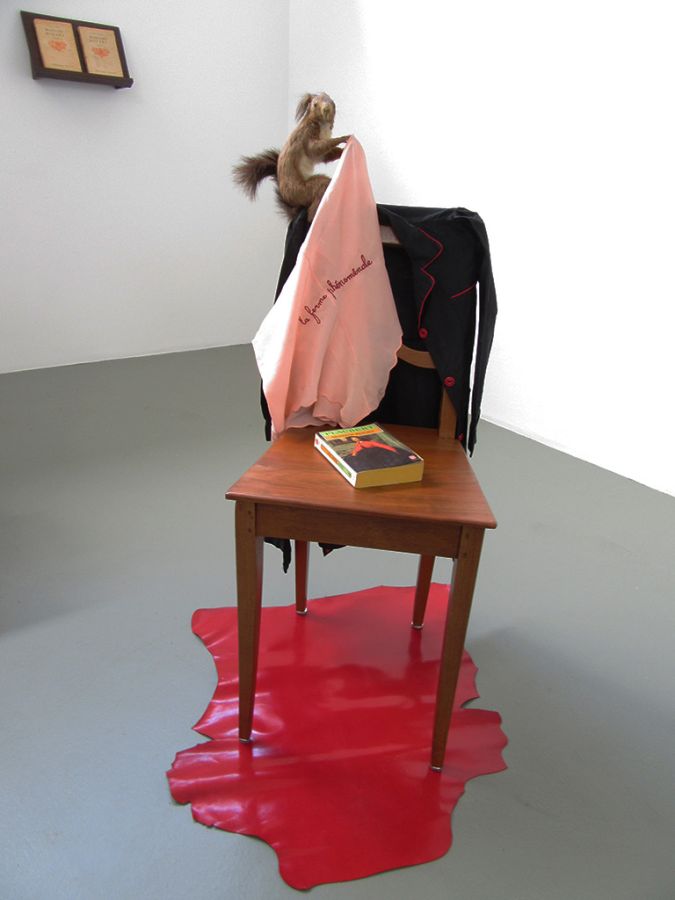

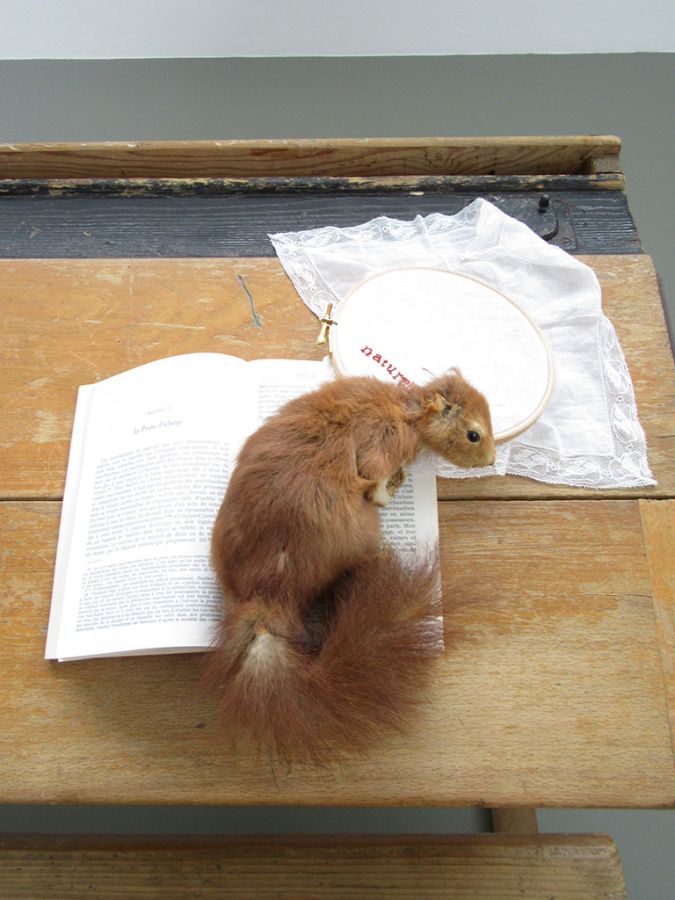

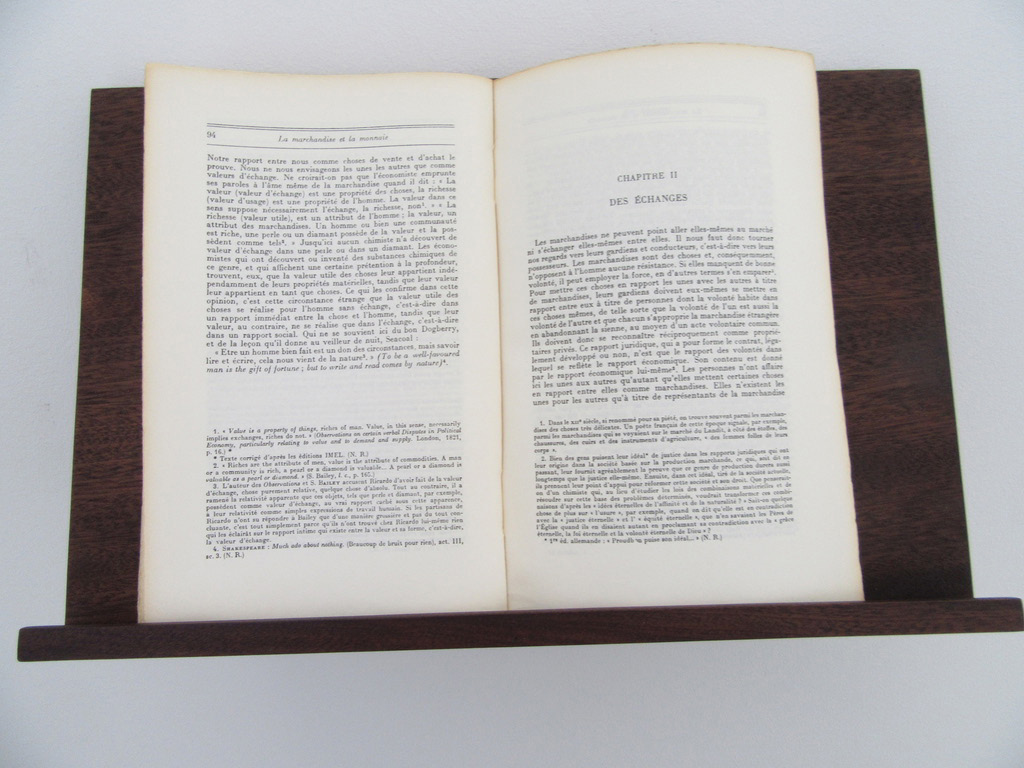

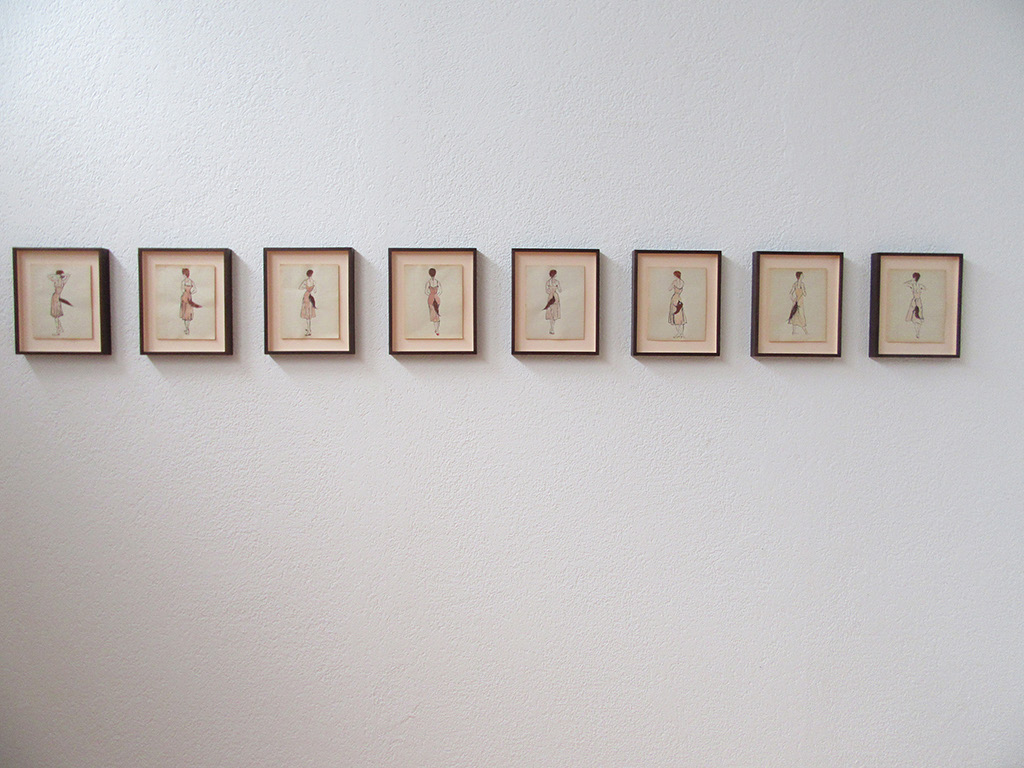

Vues de l'exposition La Forme Naturelle, Galleria Edizioni Periferia, Luzern, Switzerland, 2020

Photo: Sharon Kivland

The works on display and their arrangement were conceived for the space of Edizioni Periferia, following the exhibition at CIRCUIT. They may be considered as a series of stagings and restagings, often with familiar characters who assume new roles, concerning feminised reading, sexuality, and education.

In the hall women’s knickers, antique, pink silk, embroidered in red soie de Paris in Ecolier script, with the phrase je suis une femme moderne are suspended in beaks of birds (a buzzard, a jay, a thrush, a pair of doves…).

If the visitor continues through the silk and birds, s/he will arrive at something a little like a schoolroom. Eight simple and beautiful wooden chairs are arranged on red glacé leather skins. From the back of each chair hangs a blouse d’écolier, the smock or overall uniform that is no longer worn in schools. On each of eight chairs there is a squirrel holding in its dear little paws culottes in varying shades of pink, embroidered in red soie de Paris and Écolier script, with a phrase signifying the lovely object that is the commodity, showing the mutable forms taken by mademoiselle la marchandise. You know this already, of course. On each chair is a paperback copy of Madame Bovary, each cover giving a certain impression of ‘Emma’, according to the time it was published. On a school desk the less diligent squirrel has made a bed of Capital, and fallen asleep, her embroidery (a handkerchief: la forme naturelle) unfinished. There is also a pair of red kidskin slippers, though for the life me, I do not know why.

On one wall, there is row of eight books on a lectern, paperback copies of Capital. Opposite, two more lecterns, again with Capital. Around the other walls runs a frieze of black and white posters depicting, alternately, the faces of young girls and the silk and lace-clad torsos of women, take from French fashion journals of the 1950s. It is as if the girls are looking for models in the corps morcélés, in the bodies of adult women, a trait, an identification. The girls are laughing sometimes.

If the visitor turns instead to the room on the right, there is a display of four series of drawings in ink and watercolour on pages torn from old school exercise books:

1. Liseuses de Capital, which you know already, and which has been bought by the Musée des beaux-arts in Brest, I am very happy to say, as it will keep my press going for a few future books, as well as paying for paper from Ruscombe Mill in Margaux for new drawings of beautifully-dressed women with bloody hands—my bacchantes.

2. Les premier rouges depicts young girls wearing the New Look, Dior’s image of radical femininity, achieved by tight-fitting jackets with padded hips, petite waists, and A-line wide skirts. The clothes have been coloured in with red lipstick, the grease of which oozes through the paper; it will continue to do so, eventually destroying the paper,

3. La Femme-Renarde (The Fox-Woman) depicts women from behind, wearing pink slips that are cut to allow their bushy tails to emerge in an exuberant fashion. Their hairstyles are rather foxy too, as is the hair under their arms. They do not attempt to conceal their unruly hirsute sprouting, which is not constrained. They may be women turning into foxes, or foxes turning into women. They are mutable forms, like commodity in Capital. They are accompanied by a set of eight pink girdles dangling from the horns of deer, from which the unconstrained tail of a fox has emerged—its brush.

4. Liquette ninque depicts women with snakes. They are clearly taking great pleasure in each other’s company. The title is a hapax legomenon from Raymond Queneau’s novel Zazie dans le métro, a story about a young girl’s first visit to Paris, where she wants to travel in the metro, which is on strike, and is interested in perversion. It occurs in a discussion about laundry, the recurrence of dirt, as a play on words. The psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan refers to it in relation to the phallus and the snake (he is discussing the hallucinated snakes of Anna O. in Freud & Breuer’s book on hysteria).

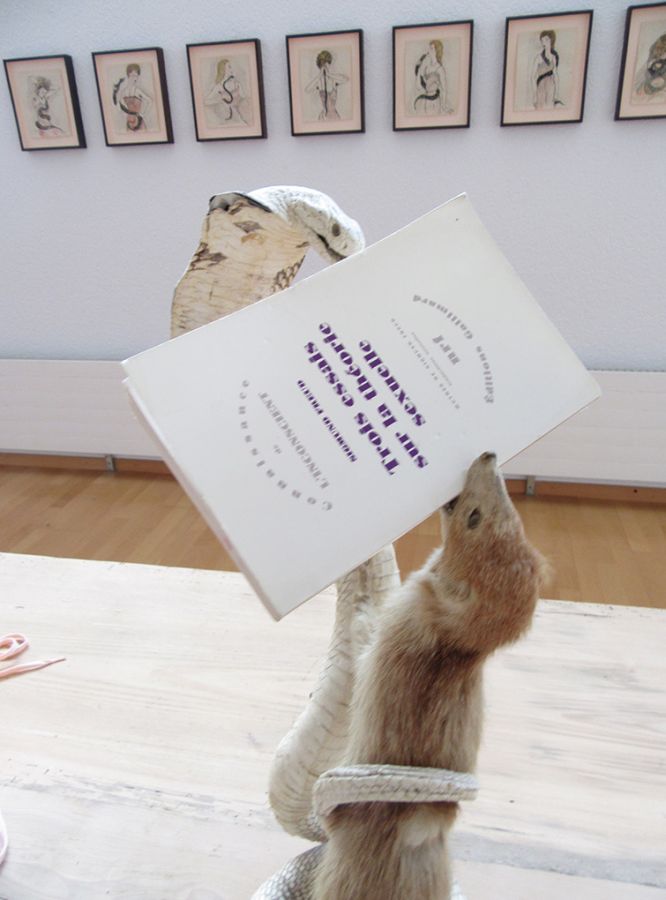

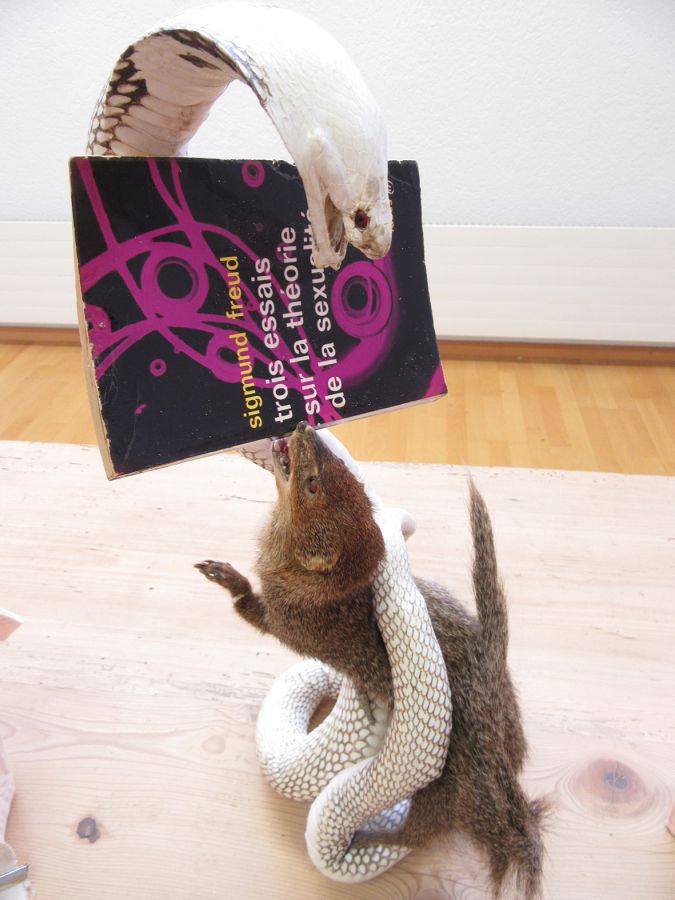

On a long and exceptionally lovely wooden table in front of these drawings are four paired creatures, snake and mongoose. Two mongooses are fighting off reared cobras with a copy of Freud’s Trois essais sur la théorie sexuelle, while two others have failed in their struggle, their opened books cast aside as serpents entwine their bodies. Birds perch on corsets, designed for children, to curb the excessive body of the little girl, her polymorphous perversity.

At the door, to one’s right, one is greeted by a fox head, holding an embroidered silk bed-jacket, a liseuse, in his jaws. The text is from Maréchal’s tract, which I am sure is a masterpiece of irony. Of course, it is interesting that it should be conceived of as anything else, that it should be taken as a serious proposition.

In the library to the left of the hall, five short films, entitled Coquetteries, play endlessly, for a single viewer seated in a beautiful armchair. In each, a single page in a French lingerie magazine is tracked from neck to knee or foot, slipping over and down the garment, a negligée, accompanied by a voiceover reading a description of the lingerie trends of the season. The voice is that of my son’s, who was instructed to sound like General de Gaulle and the emissions from the underworld on the car radio in Jean Cocteau’s film Orphée, and it is to his credit (and mine, I think, maternal job well done), that he knew exactly what I meant. The sound seeps through the entire space of Periferia.

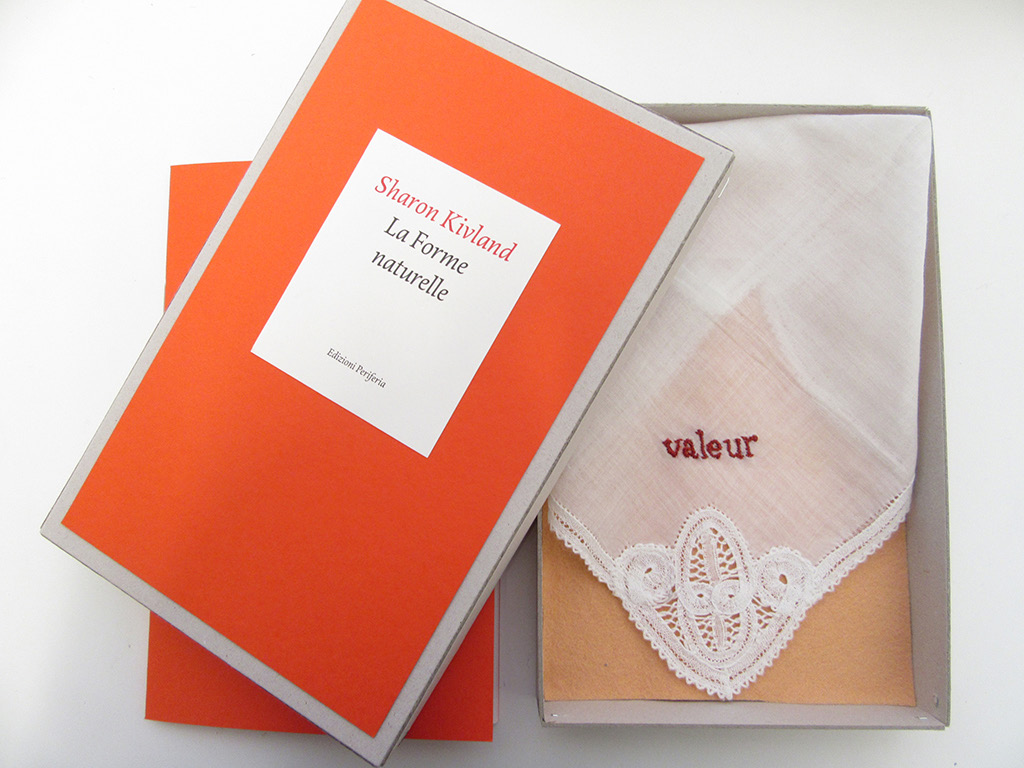

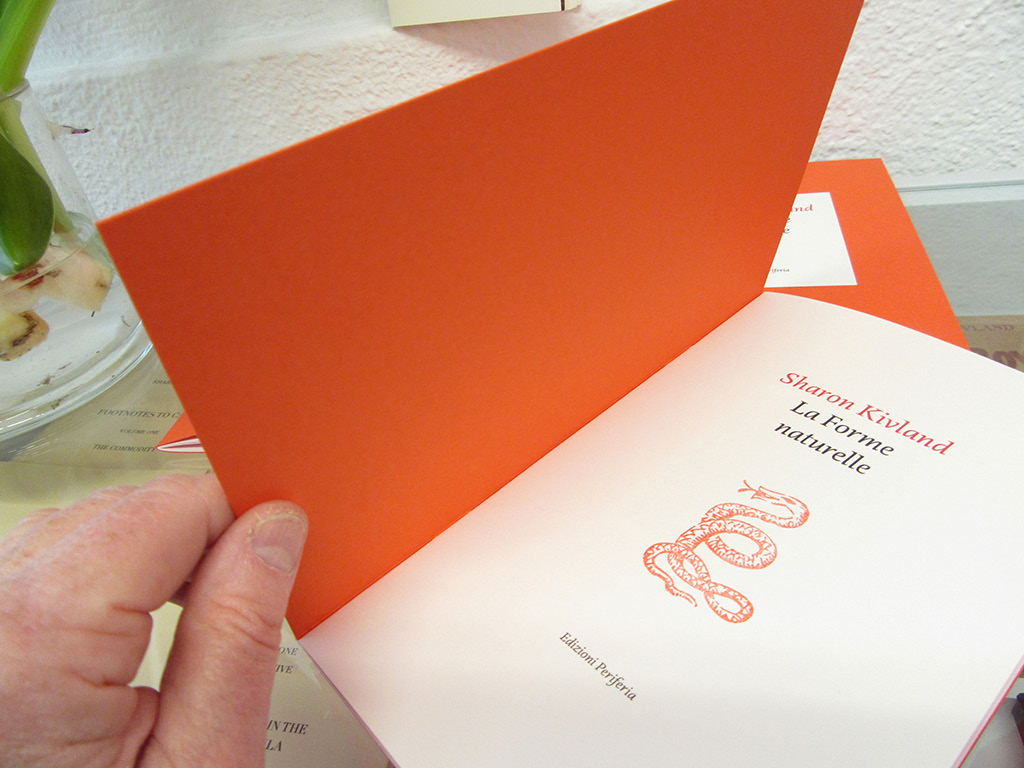

From the accompanying edition in Edizioni Periferia’s MINIMONO series, ten booklets are boxed with an antique handkerchief embroidered by the artist in red soie de Paris and Didot script, each with a characteristic of the commodity (« naturelle », « phénomenale », « sociale », et cetera.).

There was no opening event nor any subsequent event as COVID closed everything down. There was a dinner, however, with soup, and Inès and Gianni danced a tango. A good time was had by all, as we always do.

The first thought of these works was shown in Athens in the spring of 2019, in Voyage around my room, curated by Kika Kyriakacou with Vicky Tsirou.

The drawings of the women with the tails of foxes were in an exhibition in Berlin, DISTURBANCE: WITCH, curated by Alba d’Urbano and Olga Vostretsova, from 2020 to 2021. There they were accompanied by foxes (The Foxes), naturalised, more natural than Nature, and citizens, either once or not yet women, ‘becoming’, who carry their well-read copies of Capital in their jaws or paws, wildly political intellectuals. They are endowed with life, capricious, sportive, without filiation. If those who are dead or silenced—animal or woman—start to speak, move, act, then social organisation is subject to change, with no more than the flutter of a page, the twitch of a tail, a transformation. The girdles with tails are there too, and a group of young women put on the girdles, wriggled their tails, became animal. And it is at these times that the work acts, has agency, when what is dead, lives.

In 1893 Sigmund Freud and Josef Breuer published ‘On the Psychical Mechanism of Hysterical Phenomena: Preliminary Communication’, introducing many of the ideas threaded throughout their Studies on Hysteria published two years later. In both texts, they link women to fabric with the suggestion that the daydreaming incurred by needlework ‘renders women especially prone’ to the confused splitting of consciousness that defines the ‘hypnoid state’, a potential prelude to hysterical symptoms.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau once knew a girl (he calls her a young person) who learned to write before learning to read. She began to write with her needle before she wrote with a quill. She makes only Os, nothing but, large and small, inside each other, nestling Os, os, one inside the other, always in reverse. O is the same backwards, O is a mirror. O is one inside the Other: little o, big O. We Lacanians say petit a, little other, grand A, big Other. One day she looked at herself in the mirror and though how ungraceful she looked in this constrained attitude of making her Os and threw away her quill. She no longer wanted to make Os. Her brother did not like to write either, but it was the constraint he disliked, not the ungraceful air it gave him. They tried to bring her back to writing by a trick. She was delicate and vain. She did not like to have her linen used by her sisters. Linen had to be marked, to show to whom it belonged, and no one wanted to mark hers anymore. They said she had to learn to do it herself. It was a matter of possession, ownership. It is always a matter of this.

Women once learnt to read through embroidering, as art or craft or labour, women’s work in any case, where the skill of the needlework was more important that the mastery of cursive script. There was a time that only the catechism and needlework were taught, but some demanded more, to be taught about everything. They read, and they learnt quickly. They understood forms. They assumed forms.

Vues de l'exposition DISTURBANCE: WITCH à Berlin, 2020-2021

Commissaires : Alba d’Urbano et Olga Vostretsova

Photo : Annako

Performance Les femmes Renardes lors de l'exposition DISTURBANCE: WITCH à Berlin, 2020-2021

Vues de l'exposition Voyage Around My Room à Athènes, 2019

Commissaires : Kika Kyriakacou et Vicky Tsirou